Courtesy of Texas DOT

Courtesy of Texas DOTThe COVID-19 pandemic taught the world about the existence and importance of supply chains. Empty grocery shelves and rising prices for household staples clearly revealed the importance of freight mobility and logistics. The crisis also showed that there’s no such thing as a perfect supply chain, because needs are constantly changing. Having a good Plan A is not enough. An equally good Plan B is also needed.

State departments of transportation (DOTs) play an important role in the planning and implementation of work to support freight mobility. But that work has not always been prioritized. The stress test of the pandemic and the ensuing economic recovery uncovered challenges and opportunities for state DOTs to improve their approaches and systems to better support supply chain resiliency.

A better industrial supply chain fits squarely into the mission of state DOTs to improve communities through transportation, enhance quality of life, and provide an efficient and safe transportation system. Supply chains that reliably and efficiently move products to consumers improve quality of life for the public. In addition, freight companies and employees are among the top users of the transportation infrastructure that state DOTs build and maintain. In 2024, more than 3.5 million commercial truck drivers in the United States moved 11.27 billion tons of freight—72 percent of all national freight tonnage—on roads largely maintained by state transportation agencies (1).

As those responsible for quality transportation infrastructure, state DOTs fill a key role in supporting the movement of goods. To fulfill that responsibility, transportation agencies can take the following concrete actions to support better freight movement:

- Improve understanding of supply chain networks.

- Prioritize engagement and coordination with industry groups.

- Review policies, programs, and projects to support movement of goods.

- Perform regular risk assessments for supply chain resiliency.

Improve Understanding of Supply Chain Networks

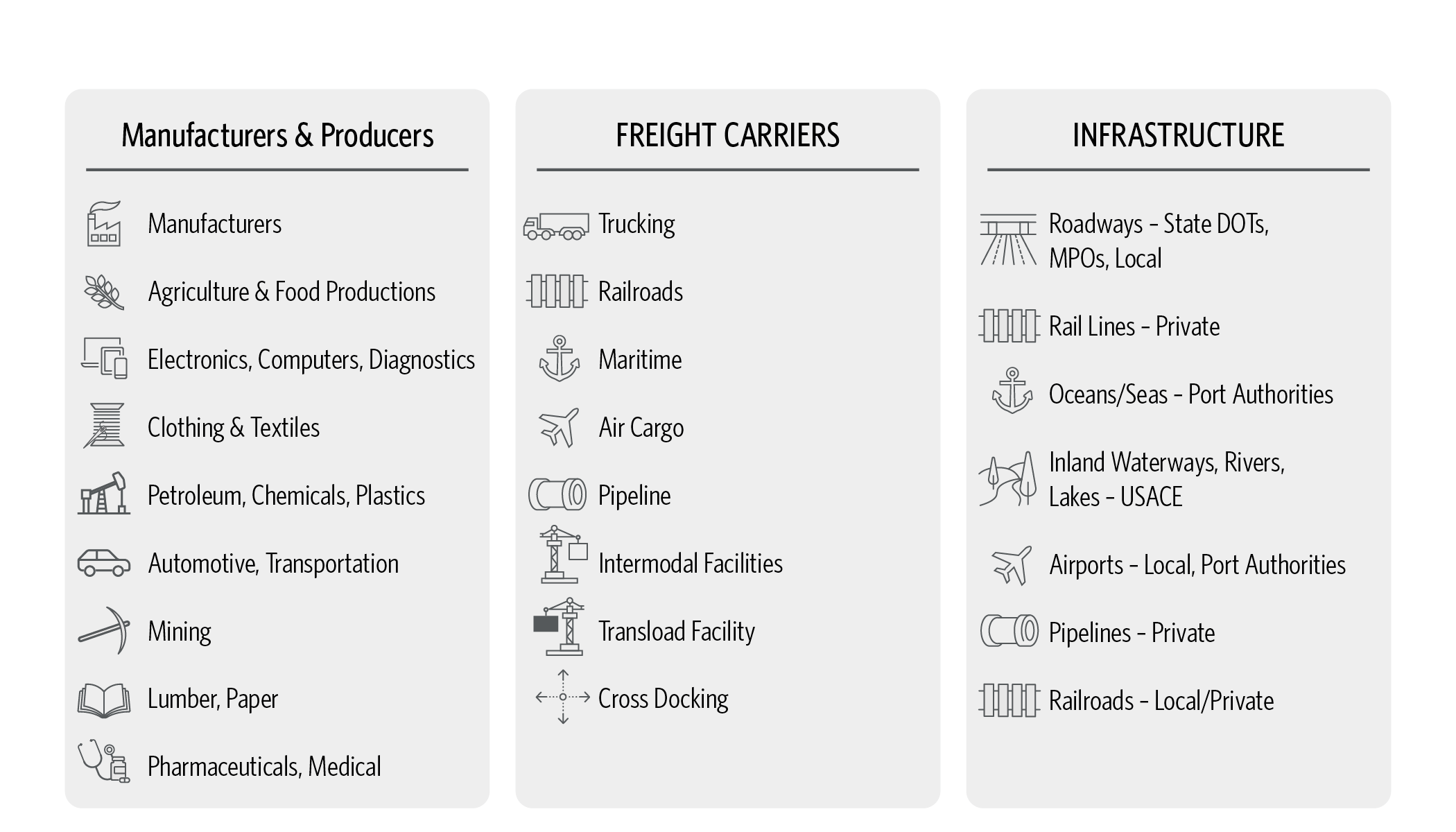

Supply chains are built on three key players: the manufacturing–production team, freight carriers, and transportation infrastructure providers (Figure 1) . All three are important, and each relies on the other two to perform their roles. Infrastructure, the platform upon which freight moves, is the component most controlled by state DOTs. Nevertheless, understanding the interactions between all three is important for public-sector decision makers and project leaders.

To quickly summarize a supply chain and its key members: Businesses create new manufacturing or production facilities and enlist carriers to transport products in response to consumer demand. Freight carriers transport the commodities, components, and products. And infrastructure owners provide the transportation foundation that allows carriers to move the goods.

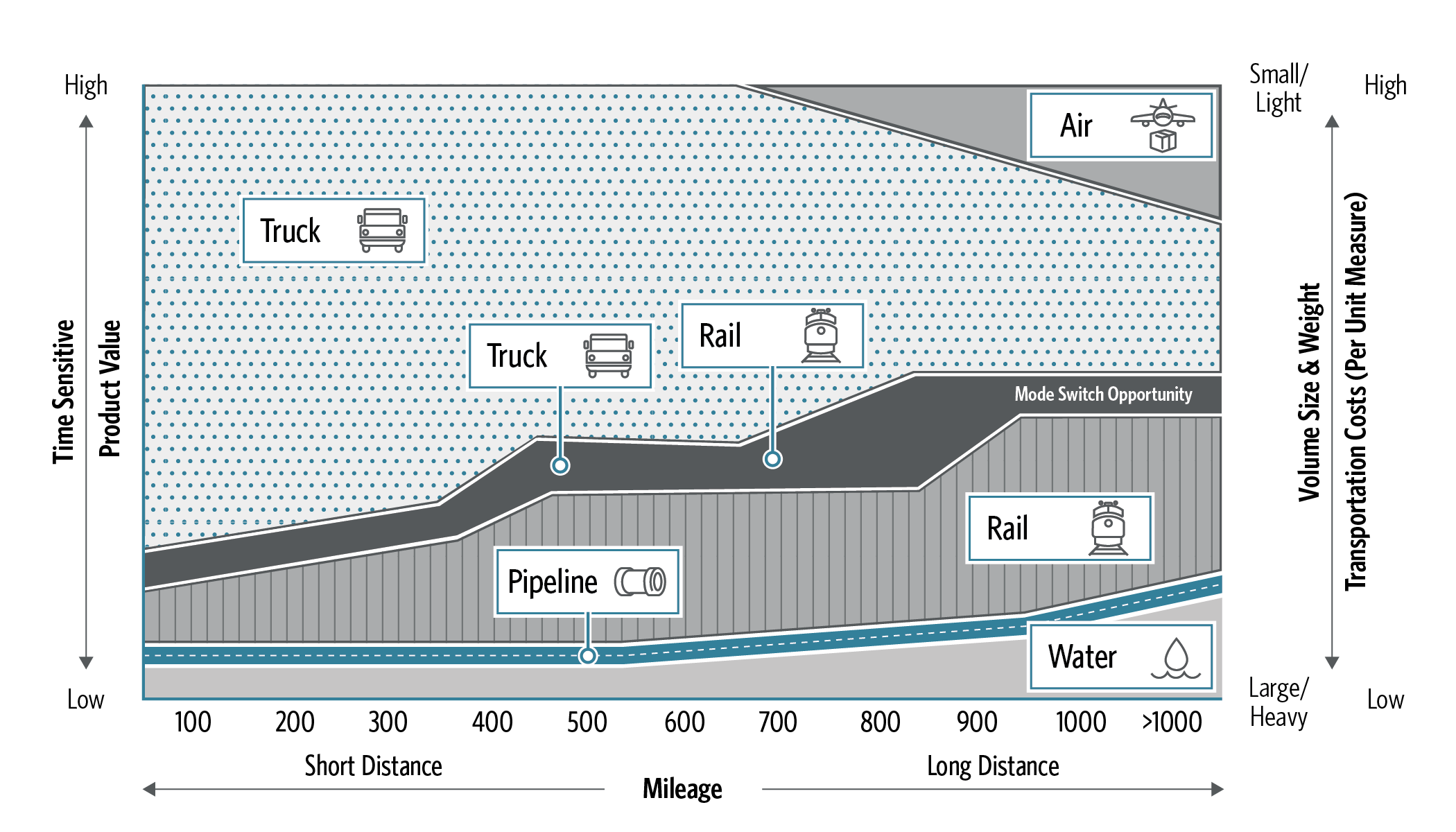

A significant amount of goods and commodities move on multiple freight modes, prompting the need for intermodal connectivity. Think of a container that goes from a ship to a train to a truck, for example. All freight modes are important, and supply chain professionals balance customer service and costs in determining the mode and carrier of choice (Figure 2 ).

States historically have embraced the responsibility of providing efficient, reliable, and safe highway infrastructure to support the movement of goods. Texas, for instance, created its system of farm-to-market roads in the mid-20th century to connect rural areas to urban centers, emphasizing the importance of distributing agricultural commodities and products. This secondary state highway transportation system now makes up more than half the mileage of Texas DOT’s road system. In Florida, the Strategic Intermodal System is the backbone of the state’s multimodal freight system.

State DOTs and local agencies bear the responsibility of developing and maintaining transportation infrastructure and intermodal connectivity in collaboration with their respective departments of revenue, departments of commerce and economic development, law enforcement, and other government entities. While state DOTs cannot directly help businesses prosper, a lack of infrastructure can hurt businesses.

The efficient movement of people and goods is critical to economic stability and growth, and cultivating a strong understanding of freight mobility is important for state DOTs in prioritizing projects and responding to the needs of the transportation system’s users.

Prioritize Engagement and Coordination with Industry Groups

Ongoing and regular communication with private industry about their infrastructure and logistics needs is critical to maintaining strong supply chains. Manufacturing and production facilities are constantly adapting to new technology, new and growing markets, changes in suppliers, and labor issues. Freight carriers are continuously adjusting to operational costs, labor availability, safety and security issues, and regulations. Transportation infrastructure that is efficient, reliable, and safe sets the conditions for the private sector to optimize freight movement.

As an example, the shortage of truck parking has been a major issue for the trucking industry for well over 25 years. But investments to increase parking facilities and the quantity of truck parking spaces—as well as to improve parking safety and security—have been slow. Only recently has the federal government taken up this issue. Good infrastructure can be a competitive advantage to businesses for getting products to regional, national, and global markets.

The transparent flow of information, regular communication, and sustainable funding are also key factors of efficient and reliable movement of goods. State DOTs, port authorities, and private-sector infrastructure owners must constantly monitor and measure mobility.

Three successive federal reauthorization bills have required state DOTs to develop state freight mobility plans and strongly encouraged states to establish freight advisory committees as part of that planning process. But too often these committees do not meet between plan drafts every four years. In turn, if meetings end and participants go silent, problems that would have been addressed tend to crop up later. Better and more consistent communication between state transportation leaders and industry can prevent issues or catch challenges when they’re small instead of when there’s already a crisis.

Review Policies, Programs, and Projects to Support Goods Movement

Ideally, state DOTs should review policies, programs, and their project selection and prioritization process to support goods movement. Supply chains are like the environment; they are everywhere. But that cannot mean they’re forgotten or ignored until a disruption occurs.

As a general rule, the great majority of freight volumes move on a comparatively small percentage of the total transportation system. Hence, states are incumbent to fund investments in an amount commensurate with the level of use.

Because freight movement supports most industries and businesses, provides economic development and jobs, and supplies citizens with the products they demand, freight-focused projects may need to be a high priority. Selection criteria—to guide project selection and prioritization within each state DOT’s decision-making process—should ideally emphasize this point.

Although state DOTs focus primarily on highways, roadways, and bridges, all modes of freight transportation are needed to transport goods and commodities. Local public investments in maritime ports (i.e., sea and inland) and airports, and private investment in railroads and pipelines, are critical for supporting freight movement. The public benefits of these freight modes are significant and reduce the impact of freight moving via truck. To support the other freight modes, state DOTs could prioritize intermodal connectivity projects that provide near-seamless transitions from one freight mode to another.

Perform Regular Risk Assessments for Supply Chain Resiliency

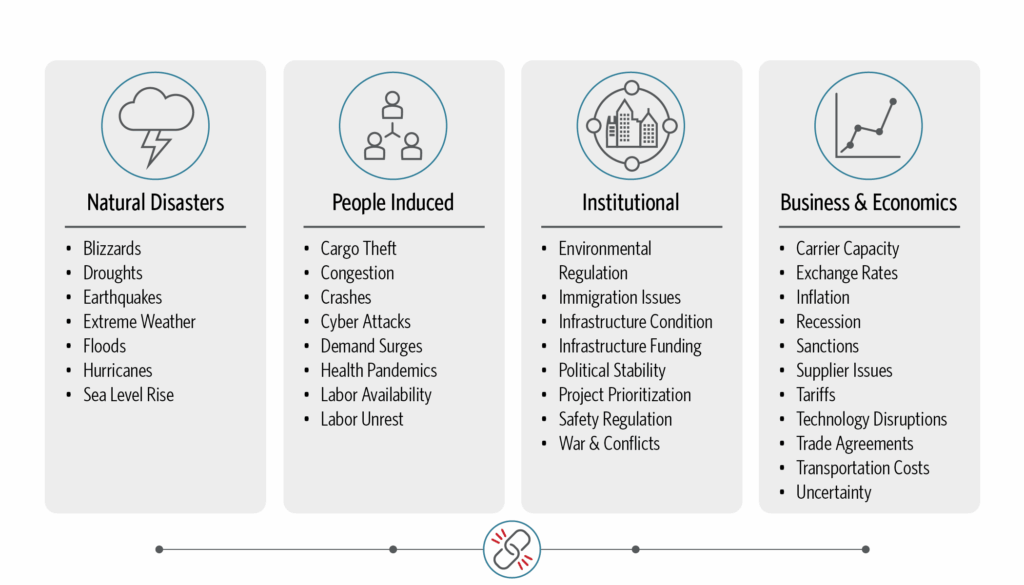

Prudent supply chain decision makers regularly conduct risk assessments to identify events that may undermine key nodes and segments in supply chains. Natural disasters, labor issues, geopolitical tensions, quality failures, and upstream and downstream supply chain disruptions (e.g., suppliers, carriers, and service providers) all disturb the efficiency and reliability of supply chains (Figure 3 ).

State planning for a multimodal freight plan starts with conducting a risk analysis and needs assessment. As part of the planning process, states should ideally identify and designate their respective multimodal freight system. Every state freight system is part of the National Multimodal Freight Network and connects with adjacent states, Canadian provinces, and Mexican states.

As recent experience has shown, severe weather (e.g., hurricanes), natural disasters (e.g., wildfires, mudslides, and flooding), human-related catastrophes (e.g., Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse), resource–funding limitations, and recurring congestion disrupt goods movement. These disruptions should prompt states to periodically conduct a risk analysis. It’s better to detect a potential risk early than to react to a major disruption later. The type and magnitude of the disruption to transportation infrastructure varies, which—in turn—affects the level of effort to recover and restore the infrastructure to an operational condition. Risk assessments, if properly developed and implemented, can reduce the recovery time or prevent the disruption altogether.

Metropolitan planning organizations are required to factor freight mobility into their long-range planning. Port authorities (e.g., maritime and airports) have master plans, and private-sector transportation owners (e.g., rail and pipeline) must continually plan and invest to solve issues and improve freight mobility. All are encouraged to think long-term and to incorporate resiliency and safety into projects.

State DOTs are also encouraged to stay focused on the primary multimodal freight system: the infrastructure needed to support private-sector production that drives the economy. Roadways, runways, maritime navigation channels, rail lines, and intermodal connectors must be efficient, reliable, safe, and secure to support supply chains. States may also consider and develop contingency plans for supply chain disruptions. These include evacuation routes, emergency resupply routes, and alternative routes to restore business continuity.

In mid-2028, for instance, the United States may experience supply chain stress as Los Angeles, California, hosts the summer Olympic and Paralympic games. July and August will be needed to prepare, execute, and recover from the games. The collective footprint of the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, airports in the metropolitan area, warehousing and distribution clusters, freight generators, and the connecting freight routes overlap the geographical locations of venues slated to support the games. Safety and security will drive many freight movement decisions—that is, how, where, and when freight can move. This will be a major test of how well a state and a metropolitan planning organization can collaborate with the private sector to effectively manage all of the aspects involved in freight movement.

A Critical Role for State Transportation Agencies

General George S. Patton once told his combat commanders, “Gentlemen, the officer who doesn’t know his communications and supply as well as his tactics is totally useless” (2). State DOTs have an opportunity to be eminently useful to their public constituents by understanding their role in supply chains and acting on that knowledge. While resilient supply chains depend on many interconnected parties, the transportation infrastructure that state DOTs maintain sets an important foundation for any success.

Not that long ago, as the year 2000 approached, the world was worried about Y2K. As the first quarter of this century comes to an end, transportation professionals may pause and reflect on the changes that have emerged to drive the economy and the supply chains that support it. Goods movement today is fast, as shippers and carriers have greatly improved efficiency via technology and better planning. Next-day and same-day delivery is possible, but supply chain disruptions in many forms are inevitable. State DOTs can best support industries and the economy by planning and investing in resilient infrastructure and operational improvements, as well as updating policies and programs that support freight-movement needs today and tomorrow. An approach that starts with strong freight knowledge, prioritizes communication with industry, and understands the risks will be resilient.